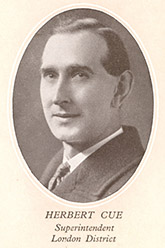

Remembering Herbert Cue

one of British Woolworth's most distinguished executives

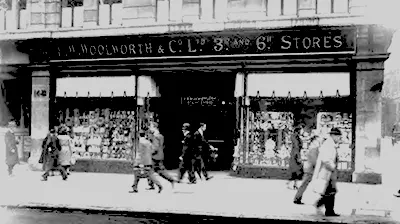

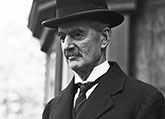

Herbert Cue earned trust and respect right across the workforce of the 768-strong store chain of F.W. Woolworth & Co. Ltd. Threepenny and Sixpenny Stores in Great Britain and the Republic of Ireland, during a career that spanned the World Wars. Many of the 50,000 people had met the self-effacing, thoughtful, yet friendly man on his regular store visits. They nicknamed the fashion supremo ‘everyone’s grandfather’.

Most Woolworth Executives were loud, ebullient and a touch dictatorial, considering themselves too important to talk to the staff. The Buyers ruled their Suppliers with a rod of iron to keep them ‘lean and mean’, demanding deference as the largest and most successful retailer in the British Isles. Cue proved that it was possible to achieve even better results by treating everyone with respect, sharing the glory, and ‘letting the value shine through’.

Like every top Manager, Cue had started at the bottom. He had learnt the ropes by sweeping the Stockroom floor and serving customers in-store. He had honed his people skills as a Supervisor and Floor Walker before stepping up into management. As the years unfolded, his career showed that unlike many contemporaries, he remembered what he had learned. If ever he heard a put-down of the long-suffering army of shop assistants who manned the counters, he retorted that "those girls are our business, without them Woolworth would not be ‘nothing over sixpence’, just ‘nothing’."

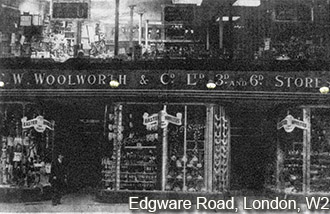

Cue had happened upon the Woolworth’s store in Edgware Road, Marble Arch, London on a trip to town, and had liked what he saw. A sign, prominently displayed in the window sought ‘smart learners’ for management careers with the business. It promised ‘unlimited earnings capability’ and an ‘opportunity to join Britain’s fastest growing business on the ground floor, learning by doing, and showing what you can achieve’. He made his way to Executive Office, around the corner in Oxford Street, opposite Selfridge’s, and applied in person.

As a married man of twenty-nine, Herbert was quite unlike most of the walk-ins at the office. Many were just fifteen or sixteen, with no family ties and a much more limited education. The receptionist spotted this at once, telling him that someone would be down to see him shortly. A moment later a smartly dressed, rosy-faced, bespactacled American bounded across the foyer with his hand outstretched. He introduced himself as Fred Woolworth, the MD. He went on to explain that several of his top performers had answered Kitchener's call and were fighting for King and Country on the Continent. He could offer a condensed training programme in the nearby Brixton Store at an enhanced salary of £6 per week as Cue was a 'more mature man', and the promise of a store of his own with the potential to earn £1,000 a year once he had learnt the ropes.

Cue took the bait and worked tirelessly in the run-up to Christmas, hoping to prove his worth quickly. He was a quick-learner, mastering the Company's complex rules, procedures and paperwork, and showing himself to be a natural leader who commanded respect both from the men and boys in the stockroom and the mainly female workforce of sales clerks and supervisors on the shopfloor. All were used to giving the run-around to the teenagers they were normally sent as learners, but quickly spotted that the new man was going places and helped him on his way.

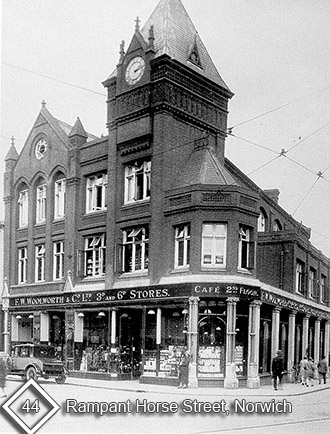

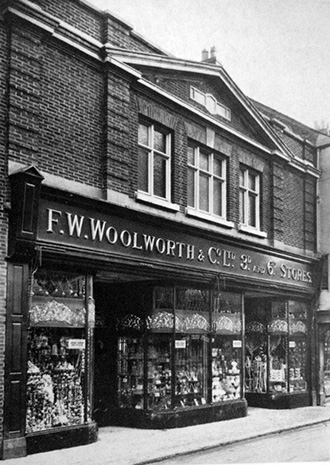

At the beginning of February he was summoned back to Oxford Street. Fred Woolworth praised his fast progress and invited him to take the helm of the branch in Rampant Horse Street, Norwich (left), which had opened a few days after war was declared. The MD explained that ‘Store 44’ was beating its budgeted sales and profit, drawing shoppers from right across Norfolk, particularly on Market Days. It was so busy that the staff were struggling to cope, with long queues building at peak times and the displays becoming depleted before the weekend.

At the beginning of February he was summoned back to Oxford Street. Fred Woolworth praised his fast progress and invited him to take the helm of the branch in Rampant Horse Street, Norwich (left), which had opened a few days after war was declared. The MD explained that ‘Store 44’ was beating its budgeted sales and profit, drawing shoppers from right across Norfolk, particularly on Market Days. It was so busy that the staff were struggling to cope, with long queues building at peak times and the displays becoming depleted before the weekend.

Cue's objective would be to build a strong team to raise its standards, engaging extra Assistants and hand-picking learners to train for future management roles as the firm expanded in East Anglia.

Cue set to work, quickly setting sales and profit on an upward trajectory. Visiting Executives were impressed not only by his new people, but also by the improved disciplines behind the scenes that made the store easier to manage. The Annual Trading Review identified Cue as a rising star and ‘thinking man’s manager’. The Board recommended a promotion before he got bored, earmarking him to take on a major store opening.

The plan was interrupted when Cue was conscripted on 22 January 1917. Changes to the Military Service Act in May 1916 broadened the pool of available recruits to include married as well as single men. The Company had discouraged its people from enlisting by continuing to pay full salaries to conscripts only. Despite stringent efforts it had failed to establish any role as a reserved occupation, and had been forced to work around such raids on its talent pool. The local Superintendent had to shuffle his Managers up the line to cover his largest outlet at Norwich, putting a woman at the helm of the smallest.

Rather than being sent to the trenches, Cue was cherry-picked for the recently formed Royal Flying Corps and appointed as an Air Mechanic 3rd Class, with service number 55288. His lively mind quickly grasped the complex schematics of the Sopwith Strutter 1½ bi-plane, the first British aircraft to carry a synchronised machine gun. They were built mainly of hand-crafted wood and sewn fabric.

Cue put his heart and soul into the war effort, going the extra mile to keep his planes in the air where they could do the most good, and learning all the tricks of the trade to keep the guns synchronised and propellers turning. His endeavours brought promotion from Third to Second and ultimately First Class Air Mechanic, making him too useful to demobilize until mid-1919.

Cue put his heart and soul into the war effort, going the extra mile to keep his planes in the air where they could do the most good, and learning all the tricks of the trade to keep the guns synchronised and propellers turning. His endeavours brought promotion from Third to Second and ultimately First Class Air Mechanic, making him too useful to demobilize until mid-1919.

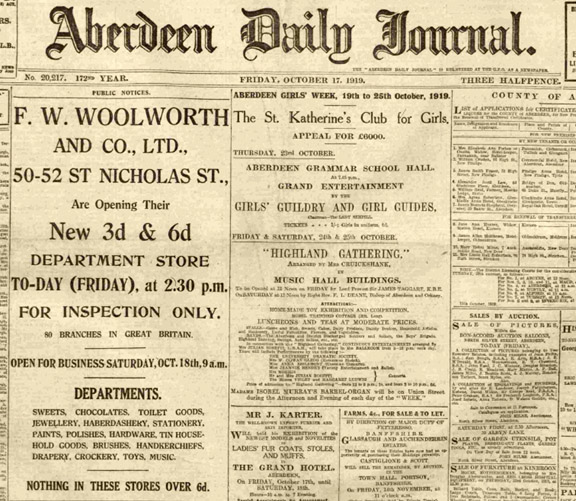

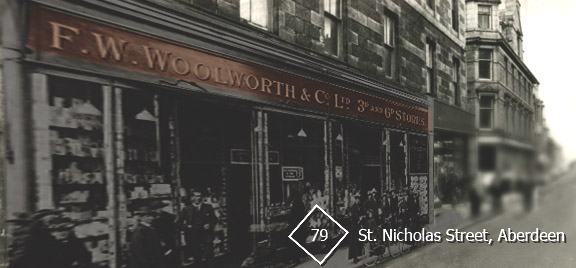

When Cue was notified that he would be released in August 1919, he wrote to notify Executive Office, expecting to be reinstated at Norwich. To his surprise, he received a handwritten reply from the MD in person. The supremo had kept an eye out for the letter, knowing Cue would have grown, but with no idea how much he would have learnt about engineering and mass production. Picking up where he had left off two years earlier, he invited Cue to take the Three and Six into new territory, pushing it 145 miles North East of its further outpost in Glasgow, to St. Nicholas Street, Aberdeen.

Woolworth did not pull his punches in suggesting the appointment. He knew it was a big ask. The store was so far away from any other that it would not be possible for neighbouring branches to help out. Most of the builders and contractors would also be newbies, and the elongated supply line would be particularly taxing. The new manager would have to source perishable items like food and plants locally. He estimated that 150 staff would have to be recruited, alongside new learners for a planned push to Inverness.

Woolworth did not pull his punches in suggesting the appointment. He knew it was a big ask. The store was so far away from any other that it would not be possible for neighbouring branches to help out. Most of the builders and contractors would also be newbies, and the elongated supply line would be particularly taxing. The new manager would have to source perishable items like food and plants locally. He estimated that 150 staff would have to be recruited, alongside new learners for a planned push to Inverness.

The MD had devised unusual remuneration options. Cue could choose to relocate at the firm's expense, or take digs for a year and get double holidays to return home periodically for his year in Scotland.

Herbert could retain an option to return home on a 'career step back' anytime, for emergencies. If requested he would have to take whatever branch was available at the time.

Herbert could retain an option to return home on a 'career step back' anytime, for emergencies. If requested he would have to take whatever branch was available at the time.

But the Founder assured his protégé that failure was "beyond improbable" based on the skills Cue has already shown and the potential of the new store.

Cue opted to take his family with him, rather than leave them in Norfolk, far from their previous home in Balham just to the south of the Metropolis. He had been separated from his wife Phyllis Ann, who he had married in 1910, and his daughter Edna Dorothy who had been born a year later, for too long. With their love and support (and a lot of unpaid free labour from Phyllis) opening day was a triumph. At the year-end record sales had been recorded and profit far exceeded expectations. Cue remained at the helm in the Granite City until January 1922, resisting a move back to the South a year earlier.

Cue opted to take his family with him, rather than leave them in Norfolk, far from their previous home in Balham just to the south of the Metropolis. He had been separated from his wife Phyllis Ann, who he had married in 1910, and his daughter Edna Dorothy who had been born a year later, for too long. With their love and support (and a lot of unpaid free labour from Phyllis) opening day was a triumph. At the year-end record sales had been recorded and profit far exceeded expectations. Cue remained at the helm in the Granite City until January 1922, resisting a move back to the South a year earlier.

To secure his services, Fred Moore Woolworth had offered an extremely generous commission rate amounting to eight percent of the store’s total profit. In the financial year 1921-2 sales broke the £75,000 mark, generating a total net profit of £15,000 and a commission of £1,200, rather more than Woolworth had promised when Cue first signed up as a Learner. At today’s prices, Cue's salary for 1921-22 was £101,280 for his service that year.

The high level of reward drew comment at the Board’s Annual Review of Trading Performance. No-one begrudged him the money. Their visits had shown a ‘happy ship, running like clockwork, with a standard that is second-to-none’. Such talent was rare and must be harnessed. The Directors were unanimous that Cue must be lured back and ‘stretched’.

The MD had the perfect challenge. Herbert was appointed Superintendent (Area Manager), not in some backwater to learn the ropes, but under the watchful eye of the top-brass as the boss of all its stores in the heart of the Capital. In the role he would receive 1.5% of all the profit generated in the branches in Woolwich, Harlesden, Ilford, Wood Green, Edgware Road, Hammersmith, Cricklewood, Stoke Newington, Acton, Chiswick, Walthamstow and Kilburn. He would be expected to deliver the same standard in these tough urban locations that he had achieved in Aberdeen, and would be invited to develop proposals for further outlets in the City.

Cue was quite unlike any other Superintendent. The Store Managers were used to the rough and tumble of sparring with their supervisor, who would bark orders, castigate tardy or scruffy shop girls and berate learners and Floor Walkers for failing to exercise the necessary control over their personnel.

Cue was quite unlike any other Superintendent. The Store Managers were used to the rough and tumble of sparring with their supervisor, who would bark orders, castigate tardy or scruffy shop girls and berate learners and Floor Walkers for failing to exercise the necessary control over their personnel.

The new boss did no such thing. He was polite and charming, and asked lots of questions. Far from remaining aloof, he got to know the staff and picked their brains for best-sellers, slow-movers and company rules that impeded their work, while gently redirecting.

Behind the scenes he thumbed the figure work enumerated on a myriad of pre-printed forms, highlighting till shortages, out-of-stocks and unexpected best-sellers. He coached his Managers to do the same, and to boost morale and teamwork in-store, delivering through the people rather than in spite of them.

He also proved highly effective at managing upwards. Despite some initial cynicism about his more laid-back approach to discipline, his more analytical style won respect at Board level. The American Directors rated him a ‘true English gent’, while the gruff Yorkshireman William Stephenson (who oversaw the rapid expansion programme) admired his attention to detail, finding the London Superintendent a strong ally in his push to open larger branches in more up-market locations.

Cue used the knowledge that he had gleaned to help Stephenson develop plans for new ‘dominant superstores’ in central London. The two devised worksheets illustrating that, by broadening the range to include more fashionable lines to complement their practical products, the Threepenny and Sixpenny Stores could prosper in the most up-market shopping streets. The pair jointly presented proposals for two new London flagships, to open concurrently in Oxford Street and Kensington High Street. The Managers would be hand-picked and their bosses would promote a friendly rivalry between them, just as Cue had with Ernest Cox, the Superintendent of the neighbouring Tooting District. Such competition was believed to maximize sales and profit.

Cue used the knowledge that he had gleaned to help Stephenson develop plans for new ‘dominant superstores’ in central London. The two devised worksheets illustrating that, by broadening the range to include more fashionable lines to complement their practical products, the Threepenny and Sixpenny Stores could prosper in the most up-market shopping streets. The pair jointly presented proposals for two new London flagships, to open concurrently in Oxford Street and Kensington High Street. The Managers would be hand-picked and their bosses would promote a friendly rivalry between them, just as Cue had with Ernest Cox, the Superintendent of the neighbouring Tooting District. Such competition was believed to maximize sales and profit.

Cue’s new Oxford Street emporium thronged with shoppers from dawn until dusk. It drew both well-to-do local office workers, and tourists from across the Empire and beyond. Its sister store in nearby Kensington attracted the self-same clientele as the neighbouring Department Stores of Derry and Toms, Barker’s and Ponting’s. The Superintendent wryly mused that Woolworth should use plain bags to save people the bother of hiding their purchases in the rivals’ wrappings.

William Stephenson, who had stepped up as MD after the shock death of Fred Woolworth at just fifty-years of age, had no truck with such false modesty. He was fullsome in his praise of Cue, his two store managers, John Whitell and Arthur A. White, and a third man, Frank Picot from Clapham Junction, who he had parachuted in goldplate the openings.

William Stephenson, who had stepped up as MD after the shock death of Fred Woolworth at just fifty-years of age, had no truck with such false modesty. He was fullsome in his praise of Cue, his two store managers, John Whitell and Arthur A. White, and a third man, Frank Picot from Clapham Junction, who he had parachuted in goldplate the openings.

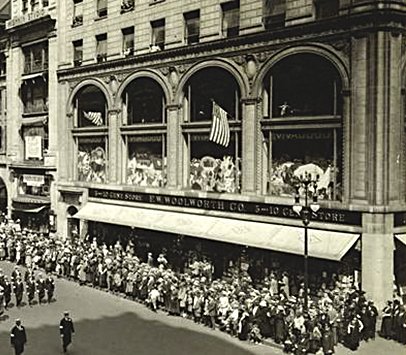

White had two claims to fame. He'd been given his first store in Gloucester, Massachusetts, USA by Frank Woolworth in 1908. Later, the Founder had also appointed him to manage Clapham Junction, UK in 1915, after its unmarried Manager was the first to be conscripted. In conversation the normally gruff Stephenson had been unusually complimentary, observing that he believed that 'FW' would have rated both of Cue's new stores as worthy stablemates of his holy-of-holies, Store 1000 in New York's Fifth Avenue (shown on the right).

In late Summer 1924, Cue’s diplomatic skills were given a stern test. After the Company Chairman, the late Founder's brother Charles Sumner Woolworth broke his long-standing rule never to leave the USA to visit London to see the new stores, the Company President, Hubert Templeton Parson decided to follow suit. Having entertained his boss, rather than do it all again, Stephenson opted to delegate responsibility for the visit to his Superintendent, asking Cue to give him the grand tour and answer the visitor's questions. ‘HTP’ had always been hard to please, and seemed sceptical about the extravagance of both the locations and premises of the new openings. The British MD felt that as a former Accountant, the President would appreciate Herbert Cue's mastery of the stores' trading performance figures. After the tour Parson thanked his host, and headed off for a motor trip around Europe before sailing back to the USA. Stephenson was forced to wait patiently until the next Board Meeting in New York to find how the tour had gone, and Parson's verdict on the new stores.

Parson reported to his Board that in London he had asked a thousand questions, and had received a thousand good answers in return. Without admitting that his fears had been misplaced, he did confirm that he endorsed plans that he had heard for two further outlets in The Strand, between Trafalgar Square and Waterloo Bridge, and High Holborn at the heart of the financial district, near St Paul’s Cathedral. He was satisfied that the ‘limeys’ had built a solid case and had proved that, far from being vanity projects, each would generate a healthy return from its first trading day.

Parson reported to his Board that in London he had asked a thousand questions, and had received a thousand good answers in return. Without admitting that his fears had been misplaced, he did confirm that he endorsed plans that he had heard for two further outlets in The Strand, between Trafalgar Square and Waterloo Bridge, and High Holborn at the heart of the financial district, near St Paul’s Cathedral. He was satisfied that the ‘limeys’ had built a solid case and had proved that, far from being vanity projects, each would generate a healthy return from its first trading day.

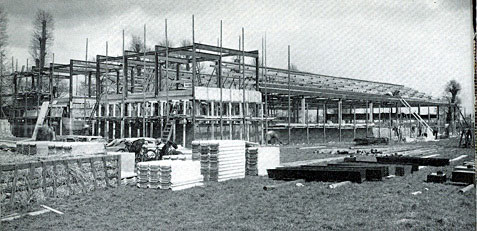

Stephenson was able to report that behind the scenes, work on the branch in High Holborn (No. 173, above) was already well advanced. It opened just six weeks after the discussion in New York, while converson work at The Strand would take a little longer and was expected early in 1925.

Cue’s new stores became the very heart of the British Woolworth, recognized by all to be ‘the crown jewels’. Competitors struggled to comprehend how such high profit could be achieved with a top price of sixpence. In a changing world, some sixty years after opening, the sale of the freeholds or long leases of the four flagships funded the acquisition of B&Q and helped to establish it as Europe’s premier DIY chain.

Cue’s new stores became the very heart of the British Woolworth, recognized by all to be ‘the crown jewels’. Competitors struggled to comprehend how such high profit could be achieved with a top price of sixpence. In a changing world, some sixty years after opening, the sale of the freeholds or long leases of the four flagships funded the acquisition of B&Q and helped to establish it as Europe’s premier DIY chain.

The success brought a healthy reward. Cue’s commission on profit continued to grow, topping a third of a million pounds at today’s prices. His skilled handling of Parson, and a further successful opening in The Strand, London WC2 (right) heralded another step up.

In 1926 Stephenson and District Manager Frank Sprague made Cue a ‘Merchandise Man’ at the Southern Office. The role had been established as a development step for Managers who had shown the potential to move from the retail side of the company to work at Executive Office.

In the post Herbert defined the range of Fashions, Jewellery, Gramophone Records and Gifts to be stocked by each of the District’s 200 stores, cherry-picking from the items chosen by the Buyers.

It allowed him to see through plans he had already laid for new branches in Camden Town, Islington, West Ealing, Fulham and Holloway Road, while gathering intelligence about store demand for the Buyers. He spent two days a week at headquarters in Kingsway, one day in meetings at the Southern District Office above his Oxford Street store, and the remainder ‘on safari’ in the stores.

During his time as a Merchandise Man, Cue made his mark by sharpening the system of “try-outs” operated in-store. Superintendents could authorise their Managers to purchase items locally to test, so long as the knowledge gained was shared with the Buyer. Cue encouraged the practice, using it to discover new suppliers, but insisted on better record-keeping. He checked invoices for the quantities purchased and cash-register reports for the exact sales. With diplomatic skill he persuaded the Store Managers that he was fighting their corner at EO, while getting plaudits from the Buyers for challenging the stores' more fanciful claims.

During his time as a Merchandise Man, Cue made his mark by sharpening the system of “try-outs” operated in-store. Superintendents could authorise their Managers to purchase items locally to test, so long as the knowledge gained was shared with the Buyer. Cue encouraged the practice, using it to discover new suppliers, but insisted on better record-keeping. He checked invoices for the quantities purchased and cash-register reports for the exact sales. With diplomatic skill he persuaded the Store Managers that he was fighting their corner at EO, while getting plaudits from the Buyers for challenging the stores' more fanciful claims.

In Spring 1929 Cue was on the way up again. He had been hand-picked to be the Southern District's 'EO Rep' - its champion at Executive Office. This was the next development step, reserved for those who had made the cut to be considered for the most prized job of all, as one of the firm's elite group of Buyers. He would report to John Ben Snow, the Board's Buying Director alongside his existing boss, Frank Sprague, the Southern District Manager and Director.

Snow took the new man under his wing, imparting knowledge about buying in exchange for Herbert's in-depth knowledge of store operations and his encyclopaedic knowledge of the financial performance on the range. It is said that his photographic recall of tables of figures was awesome to behold. That grasp of the detail dovetailed with Snow's natural flair and intuition, which gave him a sixth sense when it came to Buying. Before long Cue's plan to spend Mondays and Tuesdays at EO, Wednesday and Thursdays in the District and Fridays in the Stores had been adapted. Snow invited him to meet the key suppliers whenever they came in, wanted to accompany him on as many store visits as possible, and needed no persuasion when Cue needed to negotiate something for District Office or a store that he considered deserving.

The two men could not have been more different. Snow was loud, confident, extravagant and generally larger-than-life. In his spare time he trained racehorses and was dubbed one of the UK's most eligible bachelors. Cue was a church-warden, who loved a quiet night in at his new home in Walton-on-Thames with his wife and daughter. Yet they got on like a house-on-fire and proved to be a winning combination.

By the end of 1932, Cue had bought himself a sports car as a treat after earning a huge bonus, and Snow could recite the form of all his products just like his horses. Despite the success of the relationship Cue didn't suspect anything when William Stephenson invited him to attend the Board's Annual Review of Trading straight after Christmas. Ostensibly this was to bring fresh perspective, but there was also an ulterior motive. The two planned to offer him a job over an early dinner after the review was complete. They said that he had proved his worth and was ready to become the Buyer for departments 17 and 18, Hosiery, Drapery and Fashions. The portfolio encompassed stockings and hosiery, curtains, nets and rugs, and the small selection of made-up underclothes and large array of paper patterns that formed the Fashion Department. The MD added that Snow had already taught him many of the tricks of the trade and now wanted him to have his head. He could develop the range as he liked, with his boss available for advice if required. Cue didn't hesitate before accepting.

Initially Herbert followed the guidance that Snow had given, adopting the style of 'little boy lost' when entering negotiations, particularly for ladies undergarments. Suppliers found him charming but indecisive, noting that he appeared to rely on the judgement of his long-suffering Secretary in choosing what to buy. They soon found that the Woolworth man had a sharp, incisive mind, capable of computing many thousands of calculations a second. Not only did the new Buyer specify the quantities he required of any line by date by store to get the range on sale; he also forecast the level of repeat orders the branches would place with uncanny accuracy.

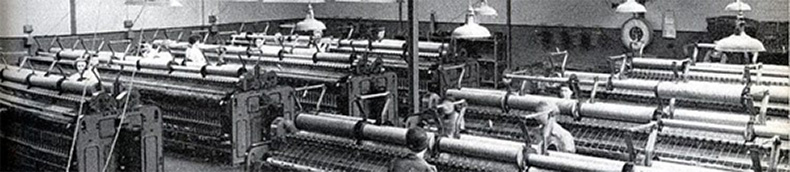

When Cue took the helm of the Fashion Department, most of its sales were generated by paper patterns showing how to make your own clothes. It carried just a few staple lines, mostly made in the factories of the north from plain Lancashire cotton. These were displayed right at the back of the shop, as shown on the left. From his store experience Cue knew that even this limited range was beset with problems, as stocks frequently ran out and, after offering excellent samples and opening stocks, suppliers frequently cut corners, sending shoddy goods when the stores placed repeat orders. This damaged the Company’s reputation, and exposed store staff to customer complaints.

The Buyer persuaded his boss that the standard buying process was ill-suited to fashion ranges. He believed that, as well as sorting out the longstanding problems, a different approach would allow him to broaden the product selection, employ new fabrics and even add a hint of haute-couture. Snow was intrigued and gladly gave the new man his head.

One of Cue’s first successes came from his dealings with Pasold Limited. Founded in the seventeenth century, the Fleissen-based supplier had established a reputation for excellence on the Continent. Its White Bear brand had become highly prized by up-market shoppers in the leading Department Stores of Paris and Berlin, but had struggled to make inroads in Britain.

One of Cue’s first successes came from his dealings with Pasold Limited. Founded in the seventeenth century, the Fleissen-based supplier had established a reputation for excellence on the Continent. Its White Bear brand had become highly prized by up-market shoppers in the leading Department Stores of Paris and Berlin, but had struggled to make inroads in Britain.

Seven generations of Pasold sons had trained as engineers before taking the helm of the family business. They had pioneered new looms and knitting machines, building their own when nothing was available off-the-shelf. This had allowed them to automate, and had been backed by an innovative framework of quality controls.

Fearing the worsening political situation on the Continent, in 1932 the firm had quietly begun to transfer its operations across the Channel to a purpose-built factory in Langley, on the border between Berkshire and Buckinghamshire. Cue became its first major customer after the MD, Eric Pasold, exploited Woolworth’s open-door policy by calling uninvited at its new, palatial HQ in New Bond Street, Mayfair, and requesting an audience.

Fearing the worsening political situation on the Continent, in 1932 the firm had quietly begun to transfer its operations across the Channel to a purpose-built factory in Langley, on the border between Berkshire and Buckinghamshire. Cue became its first major customer after the MD, Eric Pasold, exploited Woolworth’s open-door policy by calling uninvited at its new, palatial HQ in New Bond Street, Mayfair, and requesting an audience.

After an awkward initial encounter in one of the oak-panelled booths in the foyer of the smart, art deco vestibule, where the Buyers operated an open-house with drop-ins, in which the little boy lost appeared profoundly uncomfortable handling a pair of Directoire Knickers, the pair had bonded in a talk about cars and aeroplanes. As Snow had predicted, the ’automobile’ had proved the perfect ice-breaker when Herbert followed his guest's lead by making an impromptu visit to Langley.

Before getting down to business, the pair had motored to a nearby airstrip to inspect the Supplier’s pride and joy, a two seater plane. He was the proud holder of a British pilot’s licence, and had begun to ‘save time’ by flying to meetings. The factory proved equally impressive.

Before getting down to business, the pair had motored to a nearby airstrip to inspect the Supplier’s pride and joy, a two seater plane. He was the proud holder of a British pilot’s licence, and had begun to ‘save time’ by flying to meetings. The factory proved equally impressive.

During the encounter, which is given a full chapter in Eric W. Pasold CBE’s Ladybird, Ladybird: a Story of Private Enterprise, Cue revealed the traits which were to become the hallmark of his Buying. Throughout his twelve years at the helm of Woolworth’s fashion portfolio he never signed a new supplier at New Bond Street House. Instead he listened politely to any approach, remaining non-committal, and then undertook private research and a thorough unannounced factory inspection. To be selected any supplier had to have modern plant and machinery, well-paid and motivated staff, and a proven track record of quality control. Pasold’s set the benchmark for every other partner.

After the tour, Cue played his aces. Twice he was able to take his host’s breath away. Pasold later admitted that Woolworth’s order for 8,000 dozen pairs of knickers exceeded his wildest dreams. To his surprise Cue offered threepence more per dozen than he had quoted, which he had queried. After a sharp intake of breath, the soft-spoken Buyer explained that, in his experience, suppliers offered an artificially low price to obtain their first order and then cut corners to make a profit. He preferred to pay a little extra, and to insist that this was invested in capacity to fulfil the repeat orders that he hoped would follow. He had also found that such generosity placed Woolworth at the front of the queue when it came to new products.

For the next fifty years the Supplier offered every one of its new lines to Woolworth first. Despite their higher sales volumes, he made Marks and Spencer, wait until he had a decision from ‘FWW’, with Littlewoods and British Home Stores also having to wait. Ultimately Cue’s unconventional tactic also inspired the firm, which had morphed into ‘Ladybird’ after World War II, to licence the brand exclusively to the High Street chain in 1984, and to sell it outright at the turn of the twenty-first century.

On his return to London, Cue proudly shared his three golden rules for Buying at Snow’s team meeting. He recommended always visiting the factory, building rapport and playing the long game. The suggestions met with derision. Charlie McCarthy, the long-serving Irishman behind the retailer’s top selling China and Glassware range, quipped “I do declare that grandad has been caught with his knickers down!” John Snow was quick to point out that a certain Frank Winfield Woolworth had followed a similar pattern as Chief Buyer of the 5 & 10¢ more than fifty years earlier, and seemed to have enjoyed “some success”.

Cue’s creativity soon began to pay dividends. Eric Pasold put the word out that the Woolworth man was “one to watch”, creating a buzz in the rag trade. This prompted a raft of dinner invitations from the tailors of nearby Savile Row and Piccadilly.

Cue’s creativity soon began to pay dividends. Eric Pasold put the word out that the Woolworth man was “one to watch”, creating a buzz in the rag trade. This prompted a raft of dinner invitations from the tailors of nearby Savile Row and Piccadilly.

The Buyer, who traditionally brought home-made sandwiches to eat as his desk, found himself comparing the à la carte menus of Simpsons, the Ritz and the ‘In and Out Club’ (Army and Navy).

Chit-chat revealed that his hosts faced a lot of wastage in order to meet ever-changing consumer demand. They admitted that bolts of the finest silk, lace and Jacquard weave were often destroyed or squirreled away unseen.

Cue rose to the bait, offering to make the problem go away, with hard cash for the leftovers. The vendors leapt at his offer to “call my Secretary, book a visit and I’ll give you a fair price and have Carter Patterson clear the goods by the end of play”.

Cue was able to reassure his hosts that Woolworth’s sixpenny price limit was a guarantee that the High Street would not present a threat or cannibalize their market; but he kept his plans for the surplus a close-guarded secret until the deal was done.

Back at the ranch, he used the in-depth knowledge he had gathered on his factory visits to match the fabrics to suppliers with the plant and equipment to reshape it to his own designs. The leftover silks and lace were stitched to become hankies, knickers, cravats, neckties and even fancy hats. These created a storm in-store as ‘Saturday specials’, which sold within minutes of hitting the shelves. Some material was saved to create a spectacular fashion event, timed to precede factories’ wakes week holidays. Bold window displays reeled in passers-by to grab a bargain.

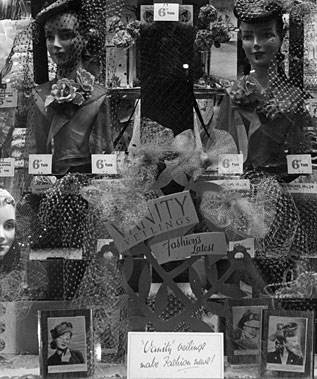

He also devised a new staple range which he called ‘Vanity Veilings’, which again featured in the windows. The off-cuts of material were chopped up and marketed as a way for canny shoppers to transform their old hats from ‘museum pieces’ to ‘Sunday best couture’.

He also devised a new staple range which he called ‘Vanity Veilings’, which again featured in the windows. The off-cuts of material were chopped up and marketed as a way for canny shoppers to transform their old hats from ‘museum pieces’ to ‘Sunday best couture’.

This tapped into the fact that hats were de-rigeur in the 1930s. Wearing a new hat was every bit as special to poor shoppers of the inner city stores as as a whole new outfit might be for a society lady.

Cue’s Vanity Veilings, comprising a hemmed strip of fine fabric, a ‘how-to’ leaflet, and a gummed envelope of pins, cost a penny to make, and flew out for sixpence.

Impressed by Cue’s string of successes, Charlie McCarthy admitted “Fair do’s, far from knickers down, I’d say it’s hats off to grandad for reminding us what Woolworth’s is for - ‘top treats for a tanner [sixpence] that everyone can afford'”.

By 1935 Cue had cut out a niche for himself as a force to be reckoned with, with an increasingly profitable and rapidly expanding range in every store. His bonus stood at an all time high.

By 1935 Cue had cut out a niche for himself as a force to be reckoned with, with an increasingly profitable and rapidly expanding range in every store. His bonus stood at an all time high.

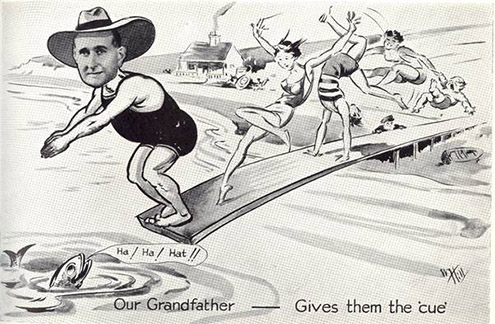

Cue still preferred the simple life, but had also begun to appreciate some of the benefits of being more widely recognised across the business. He was delighted to be singled out for a caracature in the memento for the Company's Annual Dinner. It was drawn at his table, though it had clearly been planned in advance and featured his hats and undies. Herbert particularly loved the caption, which read 'Our Grandfather - Gives them the 'cue!'

But dark clouds were looming over Europe and many challenges lay ahead.

After many years of low inflation, market prices had started to rise as Britain began to re-arm, fearing another war with Germany. The government issued lucrative orders for mass-manufactured munitions, tempting some factories to switch their production to cash in. Reduced capacity brought increased competition between retailers. Most of the big names responded by putting their prices up, while the Woolworth's Board was determined to maintain its fixed upper price limit, which was seen as the chain's unique selling proposition and the key to its success.

Throughout 1936 and 1937, the Fashion Buyer was able to contain the situation, working hard behind the scenes to match suppliers with the bolts of cloth, threads and dyes that they needed to make his garments at the lowest possible price, and showing them how to leverage Woolworth's sophisticated Supply Chain rather than using their own transport. FWW had recently signed a landmark co-operation deal with all four major railway companies to allow its goods to be conveyed quickly and reliably at a heavily discounted rate. In exchange for his concessions, Cue expected the suppliers to maintain their existing cost-price.

Throughout 1936 and 1937, the Fashion Buyer was able to contain the situation, working hard behind the scenes to match suppliers with the bolts of cloth, threads and dyes that they needed to make his garments at the lowest possible price, and showing them how to leverage Woolworth's sophisticated Supply Chain rather than using their own transport. FWW had recently signed a landmark co-operation deal with all four major railway companies to allow its goods to be conveyed quickly and reliably at a heavily discounted rate. In exchange for his concessions, Cue expected the suppliers to maintain their existing cost-price.

Some of the other Buyers did not fare so well, losing suppliers as the price of the raw materials used to make their goods rocketed. By 1938 the Buying Direector John Snow had been forced to accept a number of remedial steps, including some underhand tactics that preserved the letter rather than the spirit of the sixpenny rule.

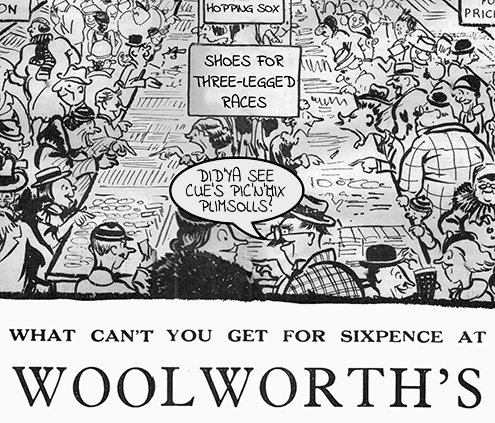

It began in 1936. The Buyer for Dept. 3 Toys began to sell the Elliot's Bloomed Blomco Camera, an all-time best-seller, as two 6D pieces, the body and backplate. The following year, the film spindle became a third part raising the true price to 1/6D (18 old pence). Snow also authorised special taxes to be charged separately. That made a pack of playing cards 6D + 3D Government Tax (9D), and gas stove lighters 6D + 6D tax, or in other words 1/- (one shilling or 5p). By 1938 Charlie McCarthy had been foreced to apply the policy quite widely on his kitchen ranges, charging sixpence for a saucepan and sixpence more for the lid, and splitting cups from sauces and gravy ladles from boats. When the cost of long white pellerene socks and black rubber plimsolls rose to 5D, Snow instructed Cue to sell them individually, using signs originally intended for ribbons, braid and electric flex which were sold by length, at sixpence per foot. (His pun doesn't work on the metric system, so there is little point showing the modern equivalent!)

Both Cue and Snow faced flack in the popular press after the price rises. It was mostly tongue in cheek, as the hacks and cartoonists were well aware that even at a shilling for a pair of socks or shoes, that was still under half the price at Marks and Spencer or British Home Stores, let alone in a fancy tailor or department store. For Cue, appearing in the newspaper felt a little uncomfortable until he was approached out of the blue to write a booklet about his excellent window displays by an American Publisher.

Snow was well-used to featuring in the gossip columns and shrugged off the suggestion that as a wealthy entrepreneur he should subsidise every pair of plimsolls sold at Woolworth to hold the price to sixpence, knowing that in the UK then as now one day's newspaper was the next day's chip wrapper, and hoping the fuss would soon blow over.

At least it made a change from their endless speculation about whether a horse from his Hoddesdon Stable would win the Derby, or which of a bevvy of beauties he had taken out on the town was his latest belle. He was just relieved that no-one commented on his most frequent dinner guest - fellow American bachelor and Director Charlie Hubbard.

At the year end, analysis revealed that after the price hike one in every five shoppers had bought a single shoe or sock rather than a pair, perhaps to spread the cost, or to replace another that had worn out or been lost. Before long there were other things to worry about.

Within a year Britain was at war. Eric Pasold’s premonition had proved all too accurate. Not only had Germany invaded his beloved Czechoslovakia, but it had commandeered his Fleissen factory to make uniforms for the SS. At least the authorities had agreed not to ask about the religion of the family members who had stayed behind, so long as production targets were met. Meanwhile the Langley Factory had added capacity so that it too could make uniforms – principally for the RAF – while honouring the commitments it had made in the High Street. Cue would later exploit this to the full.

John Snow had been on a trip home to the USA when Chamberlain had declared war, and had buckled under family pressure to resign and retire weeks before his Fiftieth birthday. Cue, who was five years older, was tempted to follow his friend's lead as his investment portfolio meant he had no need to work. But it only took a few words from the Chairman, William Stephenson, to persuade him that he was needed more than ever, and as an ex-serviceman it was his patriotic duty to stay on until the emergency was over.

John Snow had been on a trip home to the USA when Chamberlain had declared war, and had buckled under family pressure to resign and retire weeks before his Fiftieth birthday. Cue, who was five years older, was tempted to follow his friend's lead as his investment portfolio meant he had no need to work. But it only took a few words from the Chairman, William Stephenson, to persuade him that he was needed more than ever, and as an ex-serviceman it was his patriotic duty to stay on until the emergency was over.

The supremo confided that he too had contemplated retirement, until events had taken a surprising turn when he received a personal phone call from the Prime Minister. Chamberlain had politely but asserively asked him to apply his skills and expertise in mass-manufacturing as a Consultant to the Ministry of Aircraft Production, dashing out Spitfires for the RAF, reporting to the Air Minister, Lord Beaverbrook, the Canadian Press Baron. He would need to build a team of his brightest and best to help him.

The supremo confided that he too had contemplated retirement, until events had taken a surprising turn when he received a personal phone call from the Prime Minister. Chamberlain had politely but asserively asked him to apply his skills and expertise in mass-manufacturing as a Consultant to the Ministry of Aircraft Production, dashing out Spitfires for the RAF, reporting to the Air Minister, Lord Beaverbrook, the Canadian Press Baron. He would need to build a team of his brightest and best to help him.

It had all been very hush-hush. but work was already progressing well. He had requisitioned Store 234 in Church Street, Croydon as an Office, and had co-opted twenty-four store managers from across the South East to work for him. They had identified all of the core components of a Spitfire and the machinery needed for assembly and were tracking the stock and getting it to the right factory at the right time to keep the production lines running round the clock. They had built up a picture of the capabilities of each factory, and had enlisted Woolworth suppliers to provide help and even practical assistance from time-to-time. Meanwhile Stephenson seemed to spend most of his time in town, hopping between the Palace of Westminster, and government offices in Whitehall and Millbank. He had spent many hours in Government committees, gaining an insight on the workings of Government from the inside, and, he hoped, also bringing input from a fresh perspective. He had met all the major players, including Chamberlain, H.M. King George VI, and even Winston Churchill who was still out of government but making a big contribution in the committee rooms.

It had all been very hush-hush. but work was already progressing well. He had requisitioned Store 234 in Church Street, Croydon as an Office, and had co-opted twenty-four store managers from across the South East to work for him. They had identified all of the core components of a Spitfire and the machinery needed for assembly and were tracking the stock and getting it to the right factory at the right time to keep the production lines running round the clock. They had built up a picture of the capabilities of each factory, and had enlisted Woolworth suppliers to provide help and even practical assistance from time-to-time. Meanwhile Stephenson seemed to spend most of his time in town, hopping between the Palace of Westminster, and government offices in Whitehall and Millbank. He had spent many hours in Government committees, gaining an insight on the workings of Government from the inside, and, he hoped, also bringing input from a fresh perspective. He had met all the major players, including Chamberlain, H.M. King George VI, and even Winston Churchill who was still out of government but making a big contribution in the committee rooms.

In the meetings he had identified many ways in which 'FWW' could improve the home front, doing good for ordinary people and raising morale, while also building the chain's reputation and bottom line.

Stephenson couldn't resist observing that engaging with the Government would be lucrative for the business and particularly good for those Executives like Cue who got commission on the sales or profit they made. The Men from the Ministry were hoping to pick his brains on how best to implement Clothing Rationing. They feared that rations would be very meagre and yet would need a paper-trail. Perhaps Cue could think of ways to keep things simple in-store and fair for everyone. The Chairman encouraged him to open a dialogue and build a rapport with the fashion team at the Board of Trade.

Stephenson couldn't resist observing that engaging with the Government would be lucrative for the business and particularly good for those Executives like Cue who got commission on the sales or profit they made. The Men from the Ministry were hoping to pick his brains on how best to implement Clothing Rationing. They feared that rations would be very meagre and yet would need a paper-trail. Perhaps Cue could think of ways to keep things simple in-store and fair for everyone. The Chairman encouraged him to open a dialogue and build a rapport with the fashion team at the Board of Trade.

Days later Cue was helping to shape ‘make do and mend’, advising on the practicalities of rationing, and evangelising ‘utility clothing’. The Ministry lapped It up, admiring the old dog’s new tricks. He showed how to improvise new uses for salvaged cloth. This made precious material that had been damaged in air raids, or displaced when textile factories had been requisitioned to make munitions, fit for sale again.

The close relationship helped Cue to corner the market in salvage, and to box above his weight, consistently obtaining the lion’s share of whatever became available.

The Buyer was careful to share just enough to keep his major competitors on-side. Marks and Spencer and Littlewoods seemed happy enough to ride on his coat-tails in creating their own lines from salvaged material, so long as perfect cloth was distributed fairly. By stealth Cue was able to quadruple the size of Woolworth’s Fashion offer, which steadily grew from a single bay to a whole island counter in the smaller branches between 1939 and 1943.

![Woolworth shoppers could glow in the dark during World War II thanks to Herbert Cue's Luminous Dress Wear, which appeared on the drapery counters of every store. [Image: IWN] Woolworth shoppers could glow in the dark during World War II thanks to Herbert Cue's Luminous Dress Wear, which appeared on the drapery counters of every store. [Image: IWN]](/Cue/Luminousity.jpg) Clever pricing underpinned the expansion. Cue deftly navigated the end of the sixpenny price limit. He held some prices low at close to cost to build a value reputation, while adding new lines at up to five shillings a piece, ten times more.

Clever pricing underpinned the expansion. Cue deftly navigated the end of the sixpenny price limit. He held some prices low at close to cost to build a value reputation, while adding new lines at up to five shillings a piece, ten times more.

Cue had been quick to spot that customers would prefer something more durable if they were handing over their precious coupons. He added double-stitched seams and extra material in the hems, so that the new garments could be adapted for the changing seasons or to be handed down the family. Such tricks of the trade had long been features of lines from Marks and Spencer, another Pasold customer.

One of Cue’s sixpenny innovations from 1943, which was considered a joke at the time, has become a staple today. His ‘Luminous Dress Wear’ which was introduced in response to reports of countless collisions in the blackout as Britain’s cities sought to hide from the Luftwaffe, has morphed into the ‘high-visibility’ jackets worn by warehousemen, officials and even children being marched through the streets on school-trips regulated by modern health-and-safety culture. The day-glow lime greens and fluorescent orange colours adorn training shoes and athletic vests around the world, while the sixpenny originals even merit an exhibit at the Imperial War Museum (as shown above).

Looking back, the irony is that the inventor had anything but a “high-viz” career. Despite being begged to stay, as peace was restored in 1945, Herbert Cue insisted on slipping away quietly at the end of December. Company rules dictated that employees should retire at the end of the calendar year when they turned sixty years of age, and as the Buyer told the Board, "rules are rules".

Notwithstanding rationing and a severe shortage of manufactured goods throughout the World War, Woolworth sales and profits had rocketed at a much faster pace than prices. Cue’s fashions had underpinned the success and had laid the foundations for a period sustained growth and prosperity that would take the retailer to the very top of the stock market by its fiftieth birthday in 1959, out-performed only by ICI (Imperial Chemical Industries) as Britain’s largest Company.

Traditionally when top Executives retired, the Company would throw a banquet in their honour at The Dorchester Hotel in Park Lane. The Chairman would make a ‘valete’ speech celebrating their achievements, and present a gold watch from the firm, and an appropriate gift, like a matched set of hand-made golf-clubs, chosen and purchased by well-wishers. Weeks later the ‘dear-departed’ would receive a copy of the staff magazine, bearing a testimonial to their contribution on its first two or three pages for all to see. Often times the retirees had ghost-written the content to ensure that every claimed achievement was recorded for posterity. Herbert Cue had contributed more than most, yet chose to follow the example of his friend and former boss John Ben Snow, a Director since the early days, who had slipped away without a word.

Herbert and Phyllis Cue moved to the Republic of Ireland when he retired, spending a happy decade in the Emerald Isle, which had been neutral during the war and as a result was enjoying a period of prosperity far removed from the austerity and rationing back in Blighty. It is said that the couple were occasional dinner guests of Tommy Haycock, the Manager of the flagship store in Henry Street, Dublin and the head of the local buying office, for a mix of good food and conversation, that allowed them to keep a watchful eye on progress.

Ill-health forced a return to the family home in Weybridge, Surrey in Spring 1956, and admission to a local Sanatorium as Summer turned to Autumn. Herbert Cue passed away on October 23rd, having outlived and outperformed virtually every other member of his generation at Woolworth’s.

Ill-health forced a return to the family home in Weybridge, Surrey in Spring 1956, and admission to a local Sanatorium as Summer turned to Autumn. Herbert Cue passed away on October 23rd, having outlived and outperformed virtually every other member of his generation at Woolworth’s.

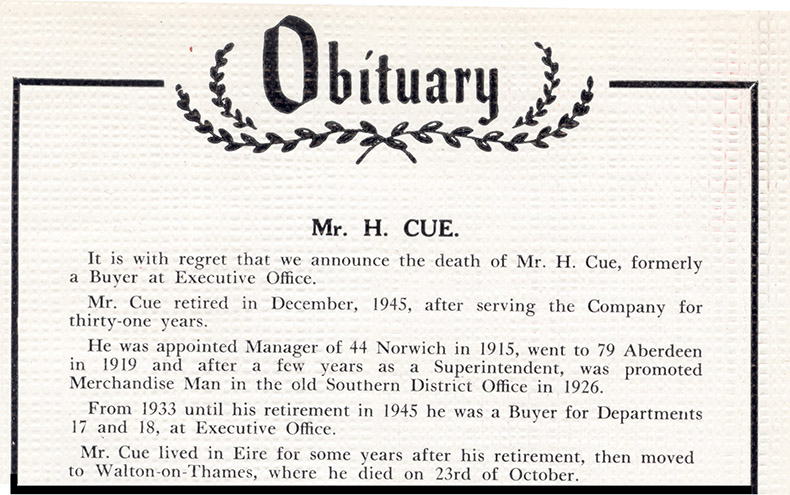

An eleven-line obituary marked his passing in the Staff Magazine issued at Christmas 1956 – little indeed for such a huge contribution to the Company, but sufficient to inspire this celebration of the career of one F.W. Woolworth’s finest sons.