The Woolworths Museum

William Lawrence Stephenson

(1880 - 1963)

William Lawrence STEPHENSON was a founder member of F. W. Woolworth & Co. Ltd. in Britain. He was hand picked for the role by Frank Woolworth as the kind of Englishman he would like on his team. He successfully anglicised the five-and-ten formula and helped the British "infant" to outgrow its parent within just twenty years. Initially Stephenson was the only British Director. He headed up Operations and Buying at the outset. He was elected Managing Director in 1923 and took the company public in 1931, becoming Chairman. He led the firm to great success in the Thirties and retained the helm through World War II, before finally stepping down in July 1948. A larger than life character, the mild-spoken Yorkshireman was a keen sailor who bankrolled the British entry in the America's Cup trials of 1932 and 1934. He was admired by his masters in New York both for the firm's spectular profits growth and for 'entertaining royalty aboard his yacht'.

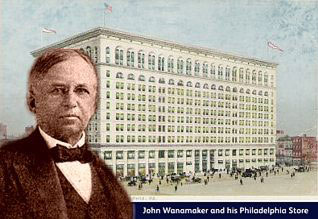

Frank Woolworth first met Stephenson on a buying trip. The young clerk came with a very special endorsement - he had been recommended by one of Frank's heroes. John Wanamaker had built a chain of large department stores in the USA, starting in 1876 with a clothing store in the abandonned Pennsylvania Railroad Depot in Philadelphia. He had pioneered price tickets on merchandise and product advertisements in newspapers, and had cultivated an international group of suppliers.

Frank Woolworth first met Stephenson on a buying trip. The young clerk came with a very special endorsement - he had been recommended by one of Frank's heroes. John Wanamaker had built a chain of large department stores in the USA, starting in 1876 with a clothing store in the abandonned Pennsylvania Railroad Depot in Philadelphia. He had pioneered price tickets on merchandise and product advertisements in newspapers, and had cultivated an international group of suppliers.

Edward Owen of Birmingham told Woolworth that the clerk had impressed Wannamaker and had helped him to secure preferred supplier status.

Woolworth's plans met with resistance in the British press. The Daily Mail compared him to P.T. Barnum, the showman of legend, who was "here today and gone tomorrow", while The Draper's Record declared that the merchant should take his shoddy goods home. Frank hoped hiring an Englishman would stem the criticism. He knew just the man. He sent a carriage from his London hotel to track Stephenson down in Birmingham. The coachman delivered a handwritten note. This read: "Please join me for dinner in London to discuss a matter that may be to your advantage. F. W. Woolworth."

Woolworth's plans met with resistance in the British press. The Daily Mail compared him to P.T. Barnum, the showman of legend, who was "here today and gone tomorrow", while The Draper's Record declared that the merchant should take his shoddy goods home. Frank hoped hiring an Englishman would stem the criticism. He knew just the man. He sent a carriage from his London hotel to track Stephenson down in Birmingham. The coachman delivered a handwritten note. This read: "Please join me for dinner in London to discuss a matter that may be to your advantage. F. W. Woolworth."

Stephenson was intrigued. He had enjoyed his chats with the larger-than-life American and had followed the success of his five-and-ten chain. He accepted the invitation and climbed on-board. That evening Woolworth offered no window-dressing. The chain might fail. His team had risked everything because they believed in the mission. He was confident that he had chosen the right pioneers, and that his second cousin Fred, backed by Miller and Balfour, would make a go of it; but they needed an Englishman. Woolworth believed that Stephenson was the right man. He promised preference shares, a Directorship from the start and the chance of a lifetime. If the venture succeeded the fledgling executives would become fabulously rich. Many years later Stephenson told a packed audience at his retirement dinner that he had not hesitated, saying "I was let in on the ground floor and never regretted it."

Stephenson took up his appointment in July 1909. He found himself in great demand. His knowledge of British manufacturing, particularly in the Staffordshire potteries, was invaluable after the buying team concluded that it would be too expensive to bring in goods from the USA. He also took responsibility for closing the deal on new buildings, following leads generated by Frank and Fred Woolworth and their American scouts. The Founder promised help from an un-named favourite in the USA who would join the team later. John Benjamin Snow soon accepted the offer and arrived in January 1910. Snow worked with Stephenson on early expansion across Northern England between 1910 and 1913, from offices above the Church Street, Liverpool store.

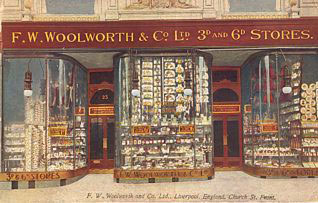

The first store opened just five months after the company was formed. Stephenson and his fellow pioneers had achieved a lot. They had dispensed with Frank Woolworth's original plan to import goods from the USA, instead sourcing virtually all of the products from Great Britain and Continental Europe. They had also found the perfect staging post to get the business off the ground. The elegant building in Liverpool's fashionable Church Street offered a huge selection of goods from its two trading floors.

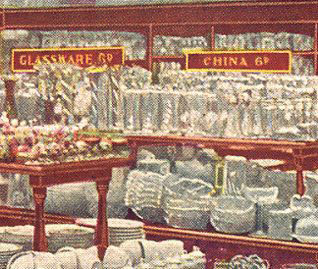

The range included confectionery from local manufacturers, housewares, 'notions' (haberdashery and knick-knacks), stationery, novelties and decorations, a small range of toys, and, to crown it all, spectacular displays of china and glass from the Staffordshire potteries where Stephenson had learned his trade. His contacts had helped to pin down exceptional items like large soup terrines for sixpence, and stacks of six dinner plates, which were also offered for sixpence a set on opening day. He had also persuaded the same people who supplied dollar-a-piece crystal decanters to Wannamaker in the USA to make a quantity available to sell for sixpence, a saving of around 75%. The gregarious Englishman was even able to secure credit terms from many of the suppliers.

By 1913 F.W. Woolworth had five stores in the London metropolitan area and established a small buying office in rented premises in Oxford Street. Bill Stephenson and John Snow were parachuted in to get it going.

Minutes of the early Board Meetings show that Stephenson took an interest in everything. He contributed on subjects as diverse as product quality and staff benefits, site and fixture selection and sales promotion. He maintained close links with stores and made a point of getting to know each manager personally. His fellow Directors knew that 'the Britisher' had the ear of the stores and gave his contribution extra weight. Over time the Yorkshireman built a reputation for plain-speaking and as a man of honour. Staff and suppliers found him scrupulously fair. He wanted everyone to get rich by pulling together. He seemed to have boundless energy, reading and challenging every report that he received.

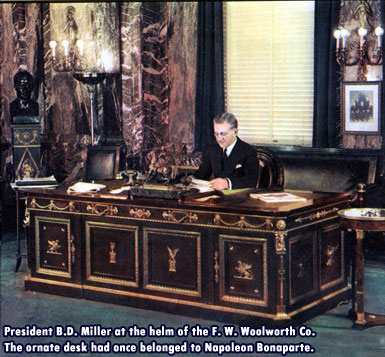

In 1923 the British business was shocked by the sudden death of Fred Woolworth, at just fifty-one years of age. The Board had not shared news of their leader's slight stroke while on a return trip to visit his mother in the USA the previous Autumn. Stephenson had lost a friend and ally as well as a boss. Careful succession planning was already in place. Fellow Director Byron Miller had returned to the USA in 1920, becoming Treasurer and Vice-President of the parent company. This cleared the way for Stephenson to take the British helm when the time came.

The Boards in both countries were in no doubt that the Englishman was the right man. Hubert Parson, who had been President of the Parent Company since 1919, made the appointment at once. The new man proved a strong leader. Less cautious than his predecessor, he was determined to accelerate the firm's expansion, and planned to anglicise the formula to achieve this. Throughout the Twenties he pushed the boundaries, challenging the authority of his bosses in New York. The parent wanted leasehold stores - Stephenson preferred ground-up builds and freeholds. The Americans wanted to raise the upper price limit to ninepence or one shilling, to match their step up to fifteen cents in 1929. Stephenson said it wasn't needed in the UK. Trading results gave the Yorkshireman the upper hand as the infant's profits outstripped the parent.

For a while it looked as if Parson might force his wayward subordinate out of office, but Miller intervened, pointing out the MD enjoyed total loyalty in Britain. Miller mediated to overcome a legal barrier. US law required overseas subsidiaries to gain approval from the New York District Court before acquiring any freehold property. Plans were laid to launch the British company on the London Stock Market, moving from a private to a public listing and selling a 48.3% stake to investors. By specifying that the reshaped company would operate under British law, the freehold issue went away. The move had a much more tangible benefit. It funded a special dividend which restored the fortunes of many stateside investors who had lost heavily when F.W. Woolworth Co. stocks had plumetted in the Wall Street Crash. Miller became President when Parson retired, while Stephenson was unamimously elected UK Chairman in 1931.

For a while it looked as if Parson might force his wayward subordinate out of office, but Miller intervened, pointing out the MD enjoyed total loyalty in Britain. Miller mediated to overcome a legal barrier. US law required overseas subsidiaries to gain approval from the New York District Court before acquiring any freehold property. Plans were laid to launch the British company on the London Stock Market, moving from a private to a public listing and selling a 48.3% stake to investors. By specifying that the reshaped company would operate under British law, the freehold issue went away. The move had a much more tangible benefit. It funded a special dividend which restored the fortunes of many stateside investors who had lost heavily when F.W. Woolworth Co. stocks had plumetted in the Wall Street Crash. Miller became President when Parson retired, while Stephenson was unamimously elected UK Chairman in 1931.

The new American supremo mused in his diary that the British subsidiary had become larger and more profitable than its parent. It seemed iniquitous that 52% of the vast profit continued to flow back to America even though the parent's total investment of $50,000 was hansomely repaid as part of the flotation. His empathy went just so far. Miller had wisely kept his British shares and had since built a significant stockholding in the F. W. Woolworth Co. parent. For him every British dividend was a true win-win.

During his time at the top Miller oversaw the parent company's transition from a fixed price retailer to a variety store. The upper limit was permanently dropped in 1935 after going up first to fifteen and then to twenty cents. He did not suggest the same move in the UK and the Irish Free State, where Stephenson's tight grip managed to force suppliers to cut costs, holding the top price to the original sixpence until after the Battle of Britain.

The British company rewarded investors for their faith in the stockmarket listing, capitalising on its dominant position in the High Street with a rapid expansion scheme, which saw a store open every eighteen days outside the Christmas season. Between 1930 and 1934 two hundred outlets were added, with a further 167 by 1939. Stephenson became a hero to investors as profits rocketed off the clock. The chain's enormous buying power gave it great leverage. As prices rose suppliers were compelled to cut costs or develop similar replacement products to stay in favour. This increased Woolworth's price differential against competitors and fueled further growth.

Success brought great rewards for Stephenson and his fellow Directors. He retained the common touch with his people while amassing a personal fortune. Company policies ensured all managers shared in the success, and that staff welfare was second to none. Support was quietly given to sales staff if they fell upon hard times or needed medical attention. British employee relations remained cordial, in sharp contrast to the situation in the USA. There staff held sit-ins and demanded better working conditions.

Success brought great rewards for Stephenson and his fellow Directors. He retained the common touch with his people while amassing a personal fortune. Company policies ensured all managers shared in the success, and that staff welfare was second to none. Support was quietly given to sales staff if they fell upon hard times or needed medical attention. British employee relations remained cordial, in sharp contrast to the situation in the USA. There staff held sit-ins and demanded better working conditions.

In the UK most employees were proud to be part of the success. Few begrudged the boss a few luxuries. Company folklore was that 'Bill' had worked his way up from sweeping the stockroom floor. A chauffeur-driven Rolls Royce allowed him to visit more stores, while an elegant J-class yacht allowed him to relax in style. Velsheda was named after his three daughters, Velma, Sheila and Daphne. Stephenson loaned it to the British America's Cup team in both 1932 and 1934. Stores sold threepenny postcards of the craft; captioned 'Velsheda racing at Cowes' they made no mention of Stephenson. Velsheda is still afloat. She has been lovingly restored by new owners and is occasionally seen sailing around New Zealand. She is said to be the finest surviving J-class yacht in the world, a venerable but very sprightly Antipodean octogenerian with quite a story to tell.

Stephenson's guests aboard Velsheda included the future King of England, Edward VIII and his friend Mrs Simpson. They were introduced by his fellow director John Snow, who had met Mrs Simpson at his club in Picadilly. Both men remained friends with the Duke and Duchess of Windsor after the abdication.

Society-living did not sap the Woolworth Chairman's energy and enthusiasm for the fine details of retailing. In 1936 he announced that planned to step back from hands-on management of the chain, appointing Louis Denempont and Charles Hubbard as Joint Managing Directors. But he gave them very little to do. It is believed that the move was prompted by John Snow's decision to step down as Superintendent of Buying. While he agreed to remain a Director, he made clear that he planned to retire and return to the USA in 1940 after thirty years in Britain and could not be tempted with a larger role and possible succession to the top job. Hubbard also announced plans to retire after his sixtieth birthday in 1938. With Snow and Hubbard out of the picture, Denempont was identified as the best candidate to take over from Stephenson when the time came.

Events overtook the careful succession planning, as Britain declared war on Germany in 1939. Stephenson backed plans by store staff to buy a Spitfire for the RAF by subscription, promising that the Board would match the employees pound for pound from their own pockets. Weeks later two Submarine Spitfires joined the Battle of Britain, badged 'Nix Over Six Primus' and 'Nix Over Six Secundus' - dog Latin for nothing over sixpence the first and second. These were the first British national assets ever to be named by the donor.

By the time the planes were commissioned the Chairman was in a unique position to secure the names. His reputation as a logistician and leader had prompted the Government to invite him to head the Ministry of Aircraft Production, reporting to the media mogul, Lord Beaverbrook. His new boss wrote to the MD Louis Denempont to say thank you for the planes ... and the company chairman!

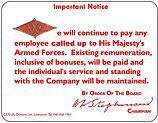

Throughout World War II Stephenson juggled his time between planes and munitions and the traumas of running the nation's biggest retailer in wartime. Denempont proved an able wartime leader, dealing with the repercussions of the long conflict. The sixpenny upper price limit was shelved in 1940 as factories switched to munitions production, pushing commodity prices upwards. The two men had to find ways of coping as one-by-one all of their male staff under 45 were conscripted for war service. The Board promised that the firm would continue to pay its men and women who were called to serve the nation, so long as they waited to be conscripted. The generous move allowed time to develop the talented women in the stores to step up into management, and to persuade many old-hands back out of retirement to take the helm again.

Throughout World War II Stephenson juggled his time between planes and munitions and the traumas of running the nation's biggest retailer in wartime. Denempont proved an able wartime leader, dealing with the repercussions of the long conflict. The sixpenny upper price limit was shelved in 1940 as factories switched to munitions production, pushing commodity prices upwards. The two men had to find ways of coping as one-by-one all of their male staff under 45 were conscripted for war service. The Board promised that the firm would continue to pay its men and women who were called to serve the nation, so long as they waited to be conscripted. The generous move allowed time to develop the talented women in the stores to step up into management, and to persuade many old-hands back out of retirement to take the helm again.

In December 1943 Louis Denempont buckled under the strain, suffering a heart attack. His death was a major blow. He had been a well-loved company man ever since 1909 and had been behind virtually every store opening of the Twenties and Thirties. His lesser-known successor, M.J. Hinckley, suffered a similar fate, passing away in the Summer of 1945. Stephenson began to believe that his retirement, originally planned for 1940, was jinxed. It seemed that each time he developed a good successor, fate stepped in.

In a moving speech at the end of the long conflict, Stephenson paid tribute to his team's service in the World War. 342 Managers and 1,963 other ranks had answered the nation's call to arms. Of these 136 had perished and another 9 were missing. He also saluted the chain's 50,000 staff who had kept the stores trading through thick and thin. While 26 stores had been destroyed and 326 had been damaged, 418 had survived everything that the enemy had to offer. He considered the commitment of staff who had done their duty as Fire Watchers, ARP Wardens, Special Constables or in the Auxiliary Nursing Service or WVS equally commendable.

In a moving speech at the end of the long conflict, Stephenson paid tribute to his team's service in the World War. 342 Managers and 1,963 other ranks had answered the nation's call to arms. Of these 136 had perished and another 9 were missing. He also saluted the chain's 50,000 staff who had kept the stores trading through thick and thin. While 26 stores had been destroyed and 326 had been damaged, 418 had survived everything that the enemy had to offer. He considered the commitment of staff who had done their duty as Fire Watchers, ARP Wardens, Special Constables or in the Auxiliary Nursing Service or WVS equally commendable.

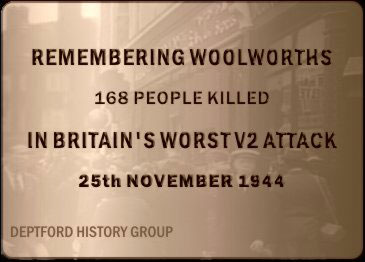

But he paid special tribute to 'Store 362', New Cross Road, which had been destroyed by a German V2 rocket on 25 November 1944. The incident had claimed the lives of 168 customers and staff. The casualties were the highest from a single bomb anywhere, exceeding the total losses across the rest of the Woolworth company worldwide.

He finished his speech by turning to the future, declaring that "now is the time to rebuild". Prosperity and further growth beckoned and F.W.W. would have its share. He called for volunteers to train ready to manage a new wave of stores across Britain and Ireland.

By 1948, when Stephenson finally stepped down, the firm was expanding again. A new generation had taken the helm. Many had seen overseas service during the war, and emerged with new perspective and determination to succeed.

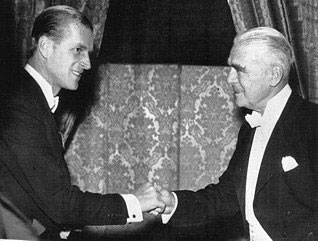

The Yorkshireman struggled to hold back the tears when he heard that more than 30,000 staff had asked to contribute to a retirement gift, and had signed cards or books of remembrance. Many of them had spoken in person to their commander-in-chief at one time or another. Investors too had contributed to a silver salver and had commissioned a portrait in oils (left) by the eminent artist Cowan Dobson, a member of the Royal Academy. They hoped that the outgoing Chairman would allow it to hang in the oak panelled board room at the firm's opulent headquarters in New Bond Street, London W1.

Modest to the last, Stephenson praised the staff. They were, he said, the most 'progressive' group in the land. He was confident that their new leaders would take them to even greater heights in the years to come. He would be keeping a watchful eye from afar as a major investor and a friend.

True to his word, Stephenson kept in regular touch throughout the Fifties, undertaking a number of consulting tasks on behalf of the new Board. He was invited to become the Commodore of the Royal Motor Yacht Club, which gave the elder statesman the perfect excuse to entertain a new generation of royalty. By all accounts the club became more efficient, while also having bigger and better parties than ever before!

True to his word, Stephenson kept in regular touch throughout the Fifties, undertaking a number of consulting tasks on behalf of the new Board. He was invited to become the Commodore of the Royal Motor Yacht Club, which gave the elder statesman the perfect excuse to entertain a new generation of royalty. By all accounts the club became more efficient, while also having bigger and better parties than ever before!

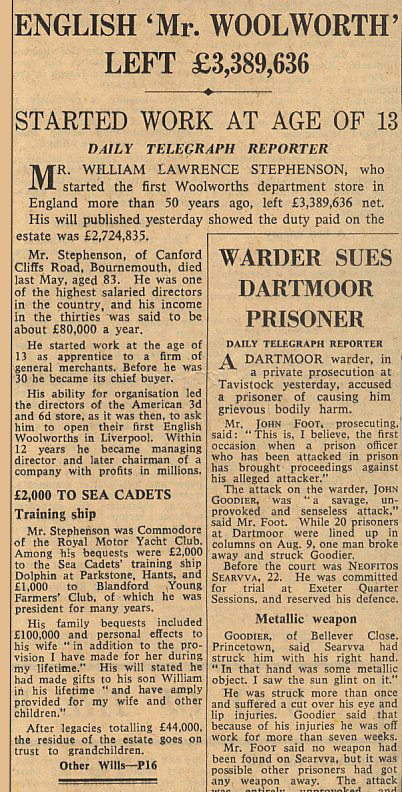

His extended Woolworth service had eaten into his retirement. The Fifties finally allowed the chance to unwind and to spend quality time with his children and grandchildren. Sadly failing health prevented him from attending the 1959 Golden Jubilee celebrations, at which he was to be guest of honour. His health rallied briefly in 1960, before a further decline set in. William Lawrence Stephenson passed away at home at the age of eighty-three in May 1963. Careful financial planning helped to minimise the death duties on his estate, which still contributed £2.7m to the exchequer, leaving bequests of £3.4m to family, friends and good causes.

Stephenson did more to shape the British Woolworths than anyone else. His commercial acumen, rigorous attention to detail and integrity along with his nurturing management style helped to build the firm from a single store to a self-sustaining chain almost 800 strong, heading to the top of the stock market. He proved a hard act to follow, as successive generations failed to capitalise on his wonderful start.

We were proud to share this biography with his grandson and granddaughter when they got in touch as the Woolworths Museum was being prepared, and are honoured to celebrate the life and achievements of the English Mr Woolworth.

Shortcuts to related content in the Woolworths Museum

1900s Gallery

US Expansion:

US Biographies:

UK Biographies:

UK beginnings:

Financing and setting up the Company

vJoin us on opening day in Liverpool

Museum Navigation